|

|

|

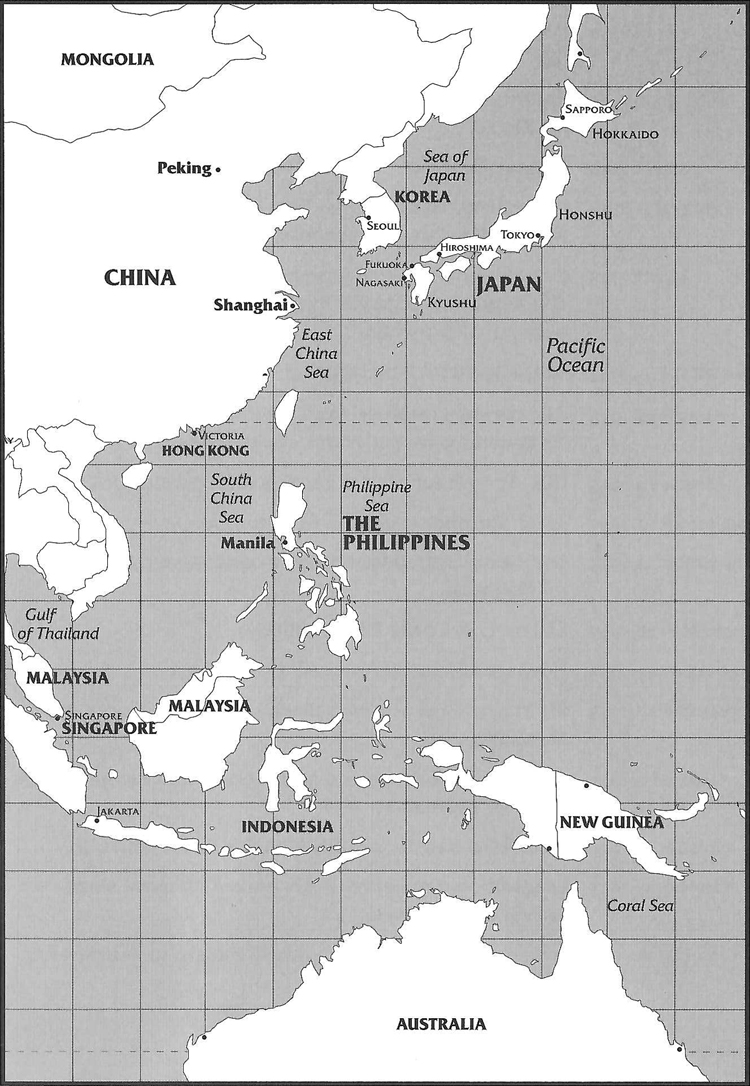

| Fourth Marines Band: "Last China Band" |

|

MIKADO NO KYAKU (Guest of the Emperor) |

| Chapter One - Introduction to Slavery - Page 1-13 |

|

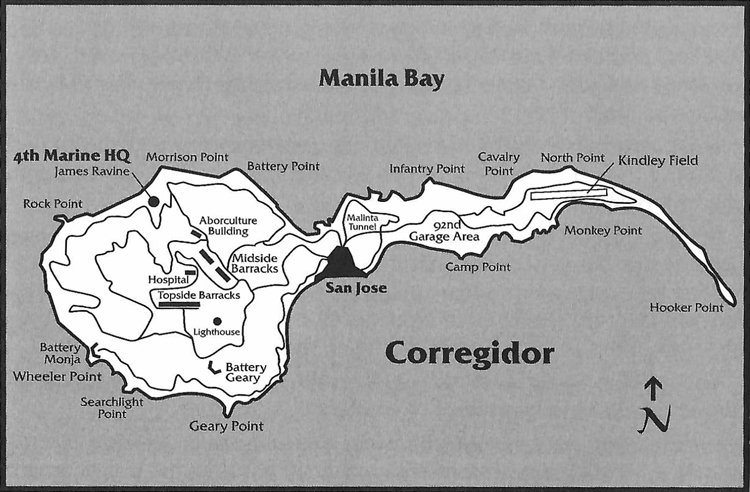

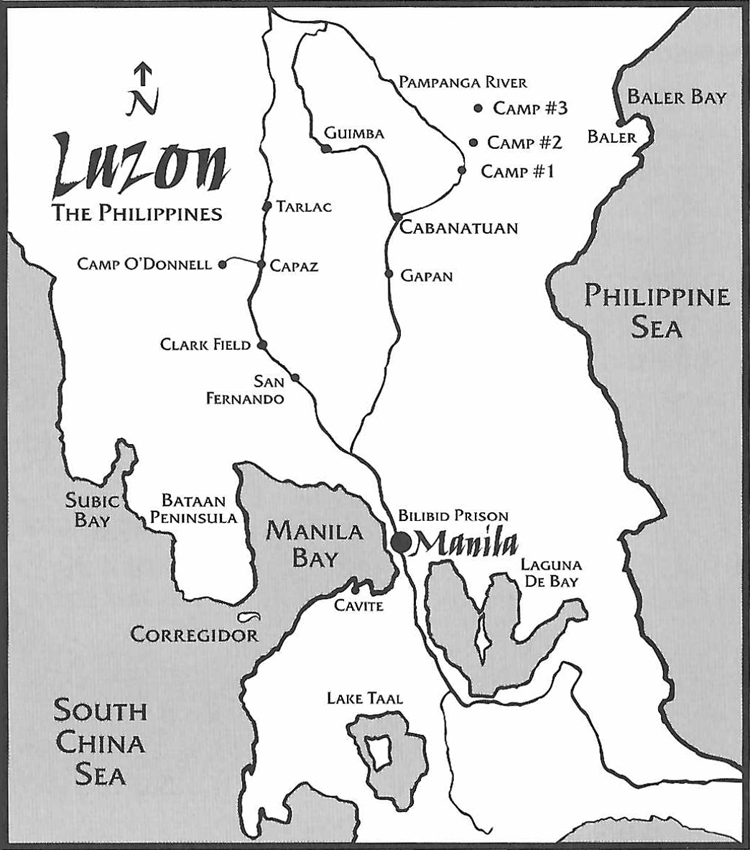

| Chapter One Introduction to Slavery The commandant had just finished giving the orders. As he strode from the platform in the big, main hall of our prison camp, his audience - men who had been farm boys and writers, and sales clerks and stenographers, and truck drivers and musicians, and professional soldiers - looked at each other, sheer fright in their eyes. After he left the room there was an unhappy buzz. "How can we be coal miners!" "I don't know nothing about coal mining!" "I didn't even know there were any coal mines in Japan." But I did. As I stood there, my face as white and my eyes as frightened as the rest, I knew. I had one of those I-have-been-here before feelings and all of a sudden I knew why. I saw myself sitting, as I had six years before, in a class room in Nebraska Wesleyan University, chewing on a pencil and listening to the professor of geology, a dignified old lady named Rose B. Clark, PhD. "It may astonish you," she was saying, "but there is brown coal under the mountains of Japan. I hope you will get there some day and see it for yourself." Well, in a left handed way, she got her wish. I was here. I was going to see the brown coal of Japan. Within the hour, I was going to mine it, bring it up from the inner depths of the earth to the fair face of this island on which I was prisoner of war, to help our enemy, willy-nilly, in his war effort. We looked like a flock of scarecrows as we shuffled two by two out of the camp gates, and down to the bottom of the hill on which our camp was perched. A long flight of stairs awaited where the Japanese flag - the Flying Meat Ball we called it- waved arrogantly. We moved hurriedly down the stairs, Americans and Dutch to the elevator head. We climbed into the grimy coal cars. "Guan gin!" someone yelled. It meant "I hope you come back." Come back? Come back to what? With each new experience in my 1,234 days as a POW I told myself "This can't be as bad as the last one," - it usually was. POW's newly returned to America from the Orient are mostly tongue-tied with the horror of their memories. With time, tongues will loosen. But nothing will be erased. No guest of the enemy ever forgets the misery he endured, the torture he suffered or to his everlasting surprise, the stupidities he saw, at his surprise at the occasional kindness of his captors. Such memories have clung to me like my shadow for many years. Corregidor, 1942... It began on Corregidor in May, 1942. Through the last days of a six month siege, we had clung to the words of President Franklin Roosevelt's promise, "Hundreds of planes ... and thousands of men ... " But we had watched General Douglas MacArthur's torpedo patrol boats chug off into the darkness of the East China Sea. Later "hundreds of planes" were droning above us, but they were Japanese Mitsubishis dropping their bomb loads on our big gun positions. The air raid signal sounded. Six of us Marines dashed to the shelter of a nearby cave. Sitting in that dark hole, our conversation turned to the message MacArthur had left us. "He said, "I shall return! Wished he'd said "I WILL return". That shows more determination", "observed Jim, the educated one. "Yeah! And he told us to trust in God - only he ain't trustin' in Him his-self, 'cause he sure enough took off!" came another voice. A great shadow loomed before us and a voice snapped: "Here! Watch your talk!" It was our ruddy, fierce looking Commanding Officer, Major James Bradley. There was less sharpness in his voice when he added, "We can't have any crepe hanging! It's bad for morale." We shut up. Three months later, the guns were also stilled; Corregidor, the impregnable fortress, was a smoldering rock. High on the cliffs above us, people were moving about amid our big, coastal artillery. By the yellowish uniforms and bandy legs I knew them for the enemy. They were waving handkerchiefs at us below just to let us know they were now kings of the mountain. The Commanding Officer ordered us to destroy our weapons and equipment; sick at heart, we did so. Quietly he thanked us for our work. He told us we would probably go to concentration camps and to be careful of what we said and did. We formed a column of fours. My mind traveled back to Shanghai and some of the light hearted talk about having to eat fish heads and rice if a war started. We were isolated from the main part of the fort and it was not until the next day after it was surrendered there that we ever saw our captors close at hand. Meanwhile we ate up everything we could get our hands on, including the little bit that had been held back for emergencies. There was no place we could go except up the sheer cliffs high above us or into the sea dashing against the rocks below or down the road into the hands of the enemy. In that sense we were already captives, but knew nothing of the terrors and horror that would begin at the end of road. For the moment there was relief from the day and night shellings and bombing that had gone on for weeks and weeks. We no longer had to sink down deep in our holes and back in our tunnels to escape the dirt, debris and shell splinters that sang their song of death over us all the time. We were fearful of what was to come but, as yet knew nothing of how our captors would treat us. We could only hope. Then, very softly, he added, "Don't lower your faces. You have nothing to be ashamed of." Good Marine, he was. (Major Bradley was killed in action on Orokyo Maru at Subic Bay, December 15, 1944 during an American air attack on the unmarked ship carrying 1619 POW's ). And we marched toward Middleside, preceded by a white flag. I had no way to know what would happen to us. I never doubted that I would survive but, that was just blind faith. The futility of the last six months had drained me. I grieved for the fall of the British at Singapore and Hongkong. A month earlier our Phil-American forces on the Bataan Peninsula had been overwhelmed by swarms of Japanese troops. Some stones had reached us that those taken prisoner there had been subjected to brutal treatment and forced marched out of the battle zones to camps a distance of 60 miles or more. Along the way some men who faltered were shot or bayoneted to death and is written in recorded history as the infamous Bataan Death March. It is one of the most horrendous war crimes of this century. I wasn't sure that we, too, were not on a death march. In a way I didn't care. I'd not only had the full five months of siege, I was weak from dysentery. "92nd Garage" Japanese kept passing us, guns drawn, going up as we went down. They didn't shoot and we were still intact when we reached the first place of captivity. We came to know it as the "92nd Garage." It was about the size of a football field, a base for seaplanes with two hangars on shore, hangars which, after they had been ripped, torn, and gutted by bomb and shell, had been used as garages for coast artillery. They would be used to store human beings-if you could still call us that. "One -two - three - four-" Our captors counted us off, as we marched in the hangars. "Sssst!" I looked up at the sound to see my battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel "Red" Anderson. Between "sssts" he was repeating again and again, "If you have any water hang on to it. If you have any water hang on to it...sssst ...I've been here 24 hours and they haven't given us any water. If you have any water ... " Not too long ago this bronzed red-headed marine had been pleasingly plump. Now he was unpleasingly gaunt. "What about food?" a man near me asked. "Just what you happen to have." answered the colonel; then he began again; ssst! if you have any water ... " "No talk"! piped the Japanese guard. "Move on! Move on!" We shuffled along, deeper in the cavern of the hanger. The warning about water worried me. About the food; I didn't care. I wasn't at all hungry. Returned POW's who have had dysentery know why. I don't remember much about the remainder of that first day. Next morning we were ordered to move out to the area in front of the hangars. At first, that seemed a blessing - to get away from the crowd. Through the heat waves, men rambled about, hunting salvage-sticks, blankets, shelter-half tents, anything to protect themselves from an insufferable sun. "Hey, Don, wanna help?" someone called to me. I couldn't answer, My tongue was too swollen. I just shook my head. I plunged into the bay to cool off. The water was dirty, salty, undrinkable. Terrible to have so much water all around when you're dying of thirst. I hardly recall much about that day either except that a Marine Corporal shared enough of his cadged water to give me strength. I had learned that water could be got from the outlets of an underground reservoir near Malinta Tunnel by anyone fortunate enough to be assigned to a work detail outside the enclosure gates. I wasn't assigned, but next morning, I fell in with an early detail of about a hundred men. The Japs counted us off. Thank God, they couldn't seem to count past 101. On the way to Malinta Tunnel, that had been the former headquarters of Generals MacArthur, Wainwright and their staffs, I picked up a gallon of cooking oil, punched a hole in the can and drained it. When we reached a reservoir, I found the outlet at the end of a long line of prisoners waiting to fill their canteens and containers. It was a slow process and the armed Japs milling around the column were grumbling and impatient. My turn finally came. I was dry, hot and dusty and ever so grateful to fill my oily can. I also filed several aluminum canteens I had carried with me for friends. A Japanese guard stood near the outlet. I accidentally squirted water on him, wetting his uniform with a mixture of water and oil. He turned on me, glowering, and I expected instant death. I knew no Japanese words, but uttered what I thought was 'I'm sorry" in Chinese. He muttered something in his own tongue, words I was to learn later probably meant, "Stupid fool!" I hurried away. I waited around where I wouldn't be noticed until I saw a detail of POWs that had worked during the night heading back for the garage. I fell in and marched back to the camp with my oily water and filled canteens. I couldn't have been more welcome if I had been MacArthur returned so soon. I doled out my liquid as though it were as precious as Chanel No.5. Now I had the hang of the place. You were part of a group of 100 including a leader and cook. If you wanted food and water it was up to you to hustle for your group. You brought all the foraged food to your cook. You went to different parts of the "Rock" - as we called Corregidor - to loot soap, mess kits, medicines and materials from abandoned camps. At first, some of the officers thought the men should do all the work. Others, like LtCol Beecher of the Marine Corps, did twice the work of anybody. Things could be obtained, but the only way to get them was to go out with your detail and hunt. We called it "scrounge." When a fence was erected around the enclosure, we thought that was the end of our hunting. We began to slip through the fence, breathless lest the Japanese guards pursue us. They would fire a few rounds promiscuously and you could hear the bullets singing. I don't think they ever hit anyone. Their marksmanship fortunately was not too good. Or maybe they didn't really want to kill anyone - perhaps they knew most of us would die soon enough anyway. Things seemed to improve for our group of scroungers. For other groups they didn't. Hundreds were wounded or sick; the death rate was up to at least five a day. The chaplains who took turns saying the services were among the busiest men in the camp, along with the doctors and corpsman organized by the POW's. The guys began to get what we called Guam blisters which became infectious sores. The cause must have been the incredibly unsanitary latrines and general lack of cleanliness. There simply wasn't enough water for washing our clothes, and bathing in the bay was almost worse than not washing at all. And then it came to our ears, which were always open for "scuttlebutt" ( unverified information-rumors), that many of us were to be sent to Luzon. This then, would be a real "death march". The scuttlebutt became official. We were to leave the next morning. |

|

| Leaving the Rock... That night it rained torrents - the first big rain since December 1941, five months before when the siege began. Those without shelter were miserable. Those with shelter set themselves to catching rainwater for baths. I still wasn't too interested in eating, but I remember that early that last morning, our cook, Marine Sgt. R. D. Harmon, made us hot biscuits and a boiler full of coffee. He was always doing something nice for the fellows in our detail, when and if, we brought him the materials to do it with. He'd even make doughnuts when he could. Despite my tremendous lack of appetite, I was prepared to say that I have never tasted anything like them since, and probably never will. It took all day to get the nearly 9,000 of us - all Americans - onto the three landing ships in the bay, about 3,000 per ship. We sat for hours and hours in those old, ratty Japanese transports. When we weren't wondering what was going to happen to us, we were wondering what would become of all the Filipino POW's we had left behind on the Rock. We sat all night. In the morning we got going and two hours later we had traversed the 15 miles across the bay. We were unloaded by Japanese landing craft onto the beach at Paranaque. We lined up in columns of four and were marched seven miles to Manila - left foot, right foot, left foot... Looking back from my place in line I could see the column stretching for what seemed almost a mile long. A light, olive drab, regular Japanese "Datsun" Army truck rattled up and down the road and we cold read its banner in English, "Asia for the Asiatics! Japan is the leader!" We men who had the strength, laughed. The marchers began to drop what they were carrying and drag themselves. The fear of Bataan was upon us. We fully expected the Japanese guards on horseback to gallop up and bayonet the weak who were being left behind. Instead, these fallen men were rescued and taken into the city in trucks. We soon found out why. This was to be a "March of Shame" and we - of all services and all ranks - were to be exhibited to the people of Manila in our filthy and weakened state. Our raggle-taggle condition would make the conquerors, spick, span, and sleek, seem so much more the victors. But it didn't work that way. "Hurrah! Hola! Okay! Hurrah!" The citizens of Manila lined the streets and cheered us. We could hardly believe our ears. And eyes. They tossed us their crude brown sugar candies and packages of their long dark cigarettes we called "brown dobbies." The conquerors were so busy trying to stop this shower of gifts that, for the moment at least, they paid us little mind. So we shouted back that "Mac" would be there in a few weeks with his Yanks and tanks. A slogan that bolstered morale until we were finally repatriated. Did we believe it? We HAD to believe it - or else we would have died of our own fear and despair. The march of shame turned out to be a left handed march of triumph and defiance. Some marchers were more desperate than others, and men reduced to such a state commit stupid things. Some even kept the china cups the Filipinas handed to us filled with water. |

|

| Bilibid Prison Late in the afternoon we were marched into the beige-colored, marooned trimmed Spanish-style structure that was Bilibid Prison on the north side of Manila. It is still there today, housing prisoners. It was like Old Home Week. For there we found some of the survivors of Bataan. In spite of their terribly bedraggled appearance, they looked wonderful to me because they had survived. They passed along rumors of battles in the Coral Sea, and they proclaimed stoutheartedly that our forces would soon be making new landings on Luzon. Those were marvelous rumors. We lapped them up and nourished our news-starved souls. But the moment of great feeling ended abruptly - our conquerors stood us up and searched angrily for the china cups; some new brutalities were handed out to those who still had them. That night the 70 in our group were given red rice in clean five-gallon containers along with a little salt and a few raw onions. It seemed a lot, so we ate only half of it. We had no more than taken the halffilled containers back to the main building when we were told that some of the enemy guards would, if given money, go into the city and buy candy, fruit and cigarettes. Most of the men had burned their money. But others had a pile of it - paper money from the Philippine Treasury which they had picked up after the Filipinos dumped their silver in Manila Bay and shipped some gold away. These men were gleeful when they heard about the purchases that could be made. Our particular group didn't care too much about buying things for we had word that we were to leave the very next morning. To where we didn't know, but we thought then that anywhere would be better than Bilibid's high, gray walls which made us feel like convicts. Well, another platoon got up before we did and left in our place. Officially we were gone, so our captors issued no food to our group that day. And we had eaten all our rice from the previous supper. We got the other group's breakfast but at noon there was nothing for either group. We heard that meat and vegetables were being issued to the men still officially present. A big, young Army lieutenant, who looked like a Notre Dame fullback and was a hero on the Rock - went all out to get some for us. We went without lunch. That didn't matter. We'd been used to, for a long time, not having lunch [rations to all United States Armed Forces Far East (USAFFE) troops had been cut to two meals a day way back in January 1942]. But as the supper hour neared and our lieutenant had still not found the proper Japanese official to handle our complaint, we began to worry ... and to ache. Bless that lieutenant! I don't know how he did it, but before dark, he and his aides hove into view lugging hunks of Carabao ( water buffalo } meat, green vegetables, and onions. Well, behind the walls of Bilibid, life was what you made it, or the hell that some other man made it for you. I wasn't exactly unacquainted with man's selfishness to man, but somehow, until that night, I thought Americans were different, The lieutenant had worked all day getting that food. It was up to us to cook and serve it. And most of us wouldn't. The men just lay around on the floor in a kind of blank stupor, volunteering for nothing, just waiting to be fed. Three of us did the trick. It made a lovely stew. Everybody ate, and then enjoyed candy and bananas the three of us bought with the few pesos we scraped together. My disgust with my fellow man of Bilibid has mitigated with the years. I know now that they were suffering from the stings of defeat and were sick with the uncertainty of the future. (I recognized then what would, 44 years later be defined as 'post traumatic shock syndrome'). Both poison. They were falling heir to the very disease the Japanese wanted us to have - apathy. Our conquerors knew that, in time, it could kill everyone in camp. With apathy and avarice among us the enemy could stand by and laugh while the stupid Americans drank one another's blood. The following morning we - the group who wasn't there - mustered out early in order not to be beaten to the gates again. We made it with no idea what awaited us. Fifteen hundred of us were marched down the mostly deserted streets toward the Manila railroad depot. A few natives watched us. This time they did not cheer. But they whispered. And they whistled songs of courage. It was up to us to supply the words. We reached a long gray freight train on a narrow gauge railway and we were piled into its boxcars. Each car would have held 20 men comfortably. But we stood, packed like sardines, 100 to a car. A guard in the center kept the lion's share of space for himself. Did we leave? No, we just stood and stood and stood for three hours, like pickles in a jar. At last our 15-car train lurched - then rumbled toward the North over a rough, barely serviceable roadbed overgrown with weeds. Through the open car doors we could see rice and sugar cane fields - wild, overgrown, unkempt. Abandoned? Probably not. The Filipinos were either lazy or being uncooperative. We jerked to a halt at every station. Natives crowded about the doors to pass us gifts, rice cooked with bits of chicken wrapped in banana leaves, mangoes, bananas, and papayas. Those closest to the doors got everything. Nobody passed anything back to the men in the rear. We began to suffer from unanswered calls of nature. During these last few days, everyone had a mighty increase in carbohydrates, mostly rice. That tended to effect us with diarrhea and active kidneys. Only a few of us carried any kind of container. We either could not make the guard understand or he chose to ignore us. He probably judged that nobody was any worse off than he. But he was accustomed to a rice diet. All day long we stood and rode, on and on and on. When at last we halted for good, although some of us were ready to drop, they lined us up for a count. We counted several times. Our Japanese could never seem to get the same number twice. Not until they did were we permitted to relieve ourselves (go benjo). "Guests of the Emperor" Now our 1500 were divided into five groups of 300 with a "captain" in charge of each, an enemy colonel in charge of the whole. He was a big fellow with a mustache and splendid military carriage. He was dressed in a neatly pressed uniform with a white open collared shirt and wore the strange Japanese army issue of the "Frank Buck" sun helmet that looked like a large, inverted hornet's nest. He had less of an oriental look than most Japanese officers I had seen thus far and had no trouble speaking English. "You are not to run away," he addressed us politely, "you are guests of the Emperor." None of us guests knew exactly where we were so I doubt anyone had an escape plan. We were marched through the streets of a city we found out later it was the big market city of Cabanatuan - and even here the natives cheered us along another march of shame, they threw us mangoes by the dozens. "You rest here for the night," the Japanese colonel told us when we were corralled in a small schoolyard. "Stay with your group. Give what money you can afford. We will purchase tobacco and fruit for you and we want you to distribute it equal." While we awaited the return the of the colonel's men and their purchases, we saw natives streaming past the compound. Without looking or speaking they would toss packages of food and tobacco over the two little strand fences. We scrambled for them. The strongest got the most. One brave woman, whose hair was streaked with gray and who smoked a long cigarette, even stole inside the fence to bring us a cake and fried chicken. A few men wolfed down the food. "But I wanted all of you to have some," protested the woman in dismay, "I will go bake more." (At two in the morning she came back with three pies.) The colonel, a sword at his side that all Japanese officers seemed to carry, invited our officers into his tent and entertained them so politely and agreeably that we wondered what was wrong. It was a first example of one of the inexplicable characteristics of our captors. Some were capable of human kindnesses. When demonstrated, it stood out and reflected a compassionate spirit of one soldier to a fallen enemy It was one of the great enigmas during my captivity that I never quite figured out. It was however, very rare. He provided Japanese cooks to prepare the rice we ate during our two meals on the schoolyard campground, plus another batch of rice to take on our march to the permanent camps to which we were being routed. "Take plenty of water." He warned, "And conserve it." At dawn we marched away, North Street eastward toward the beautiful Sierra Madre mountains that loomed larger as we grew nearer on our trek north and east of Manila. I wondered how many of our hosts knew that the seemingly cheerful natives were actually whistling us a good-bye - and that what they whistled was "God Bless America"? Well, we were marching in the general direction of America. But would any of us ever get there? On and on we slogged. The heat was depressing. Some of the men were using up their water too fast. Three fellows and I had a gallon jug. We took turns carrying it. And we took turns sipping it - just sipping. "Hey, can I have some of your water, Bud?" I recognized the man, a fellow who had been wolfing sugar. Sugar will dry you up fast. "I will give you these," he offered when I hesitated. He pulled a package of cigarettes out of his shirt. I turned to my three companions. I guess each remembered, as I did, of a time he had been given something when he needed it. Each nodded. So we gave the sugar wolfer a drink. Us four jug carriers were near the end of the line. We could see the head of the column go over and down the little foothills far ahead and then disappear around a curve. Then we saw a man staggering. I caught up with him. He was thin and wet with sweat. "You thirsty?" I asked. He shook his head. Ten minutes later he fell. We stopped to watch. Bataan? They shot or bayoneted those who were too weak to go on. They had even shot a chaplain who was trying to help a fallen man to his feet. I knew this guy was sick, that he needed water, and that he must get to his feet. I looked to my friends again. And again they nodded. So I poured a little water on his cap and put a little on his mouth. His forehead was terribly hot. He began to shiver. He had malaria bad. An escort sentry walked back. A sallow looking character, carrying a rifle nearly as long as he was tall. A flap of tan cloth stitched to the back of his Japanese regulation cap covered the back of his neck - made him look like some kind of desert legionnaire. "He going on?" He asked gruffly. We shook our heads. Two other sentries came up. We waited for the bayoneting and the shooting to begin. But the Japanese made a little flag out of a strip of cloth one took from his pocket, fastened it to a stick he found at the roadside, and stuck it into the ground beside the sick man. |

| Next: Chapter 2 - Full Text of MIKADO NO KYAKU (Guest of the Emperor) | Please Click Below for: |

| 1. Introduction to Slavery | Page 1 |

| 2. Our New Home in Bongabon | Page 15 |

| 3. To the Shade of Mount Penatubo | Page 37 |

| 4. Bilibid Prison Again | Page 55 |

| 5. Cabanatuan "Revisited" 1944 | Page 59 |

| 6. The Nissyo Maru. A True Trip of Terror | Page 67 |

| 7. Where the Birds Don't Sing and Flowers Don't Smell | Page 82 |

| 8. The Setting of the Rising Sun | Page 99 |

| Epilogue | Page 117 |

| Return to MIKADO NO KYAKU Introduction Page |

| Additional Fourth Marines Photos and Information |

| Please Click Below To Return To: |

| EMAIL: info@4thmarinesband.com |

| ©2000-2021 lastchinaband.com. All rights reserved. |